Every October, the Society of North Carolina Archivists celebrates Archives Month! This year’s theme, What Puts You on the Map?, brings to mind Duke University Medical Center’s SEDO system, a wayfinding system rolled out in 1971 that left its mark on the hospital.

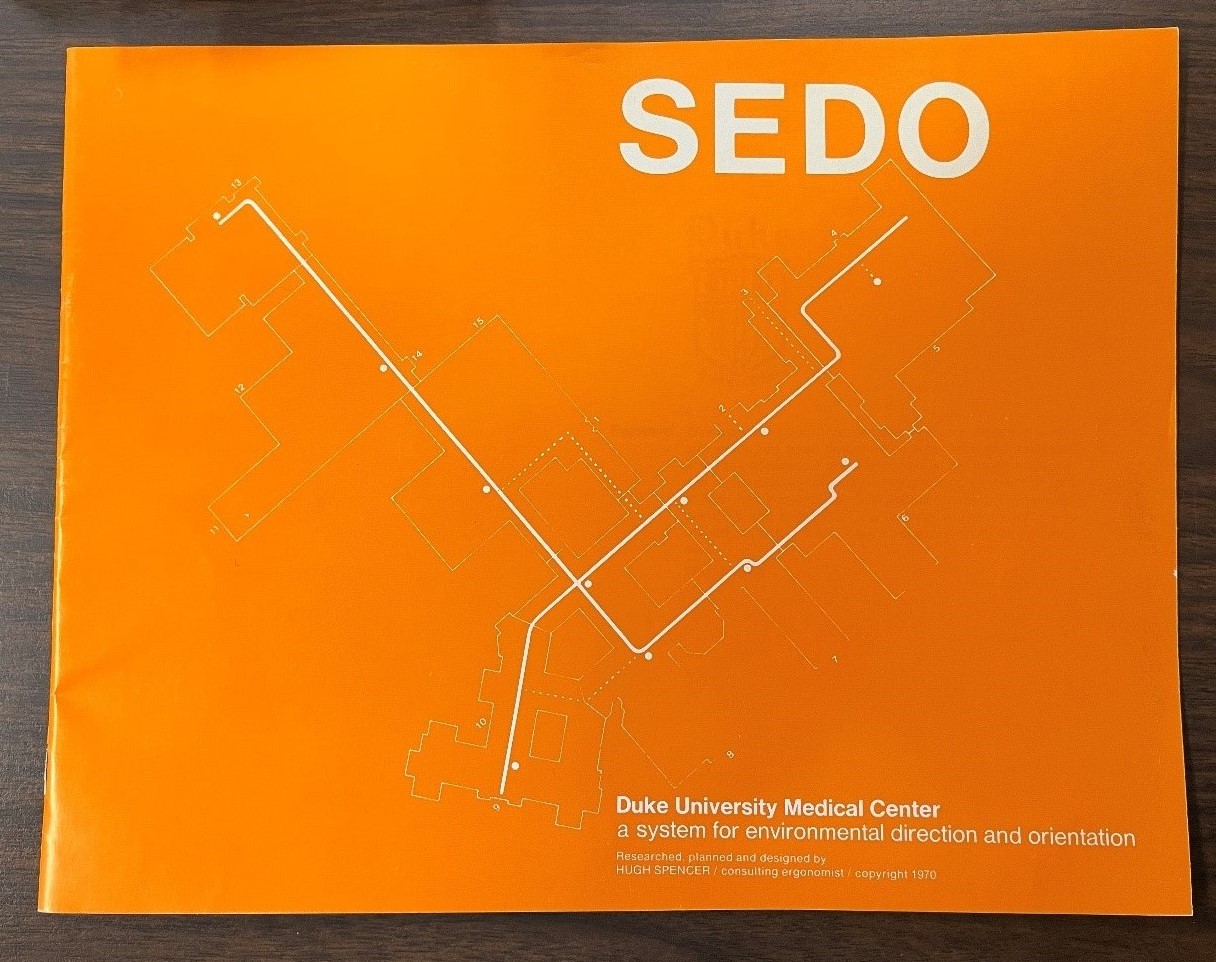

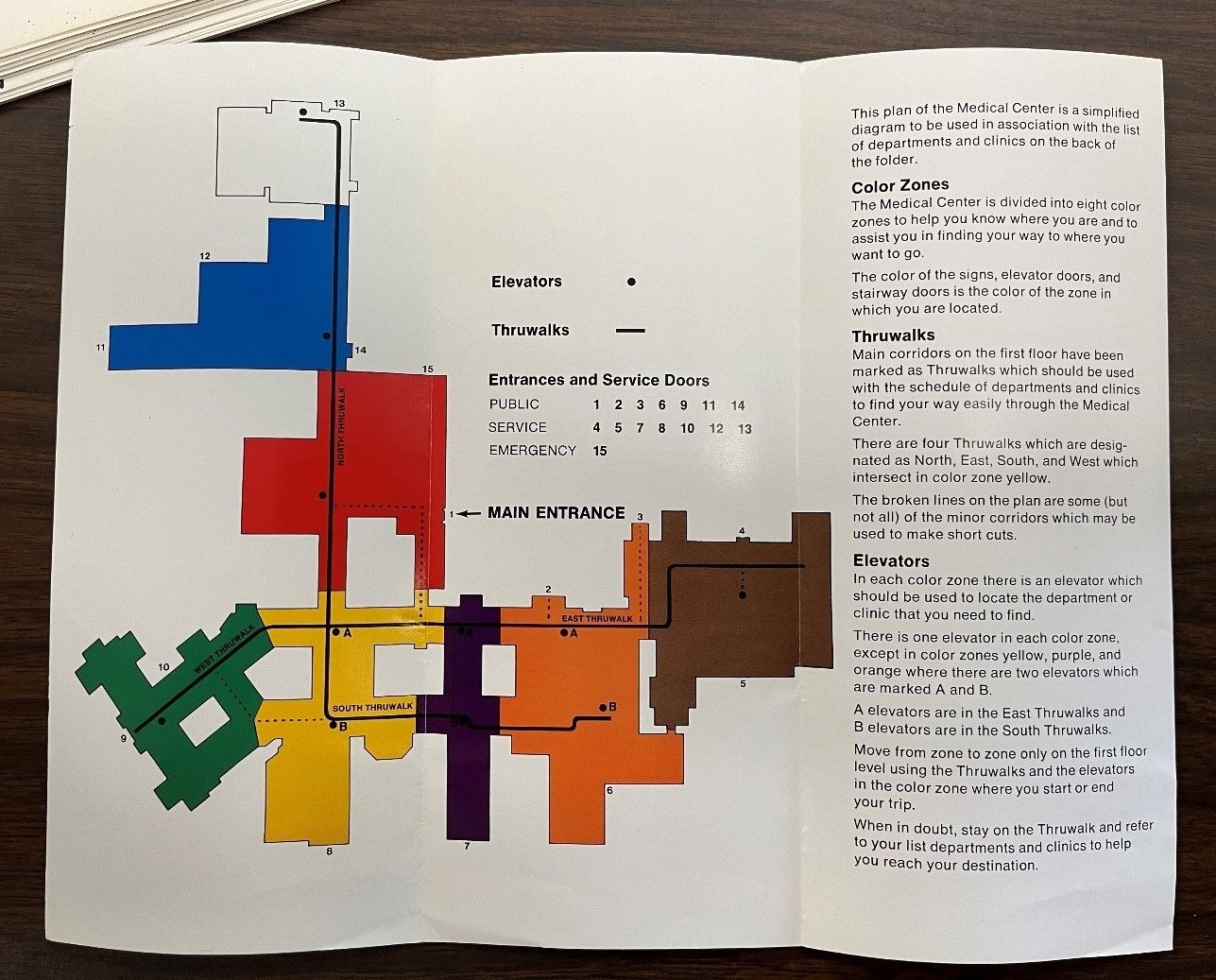

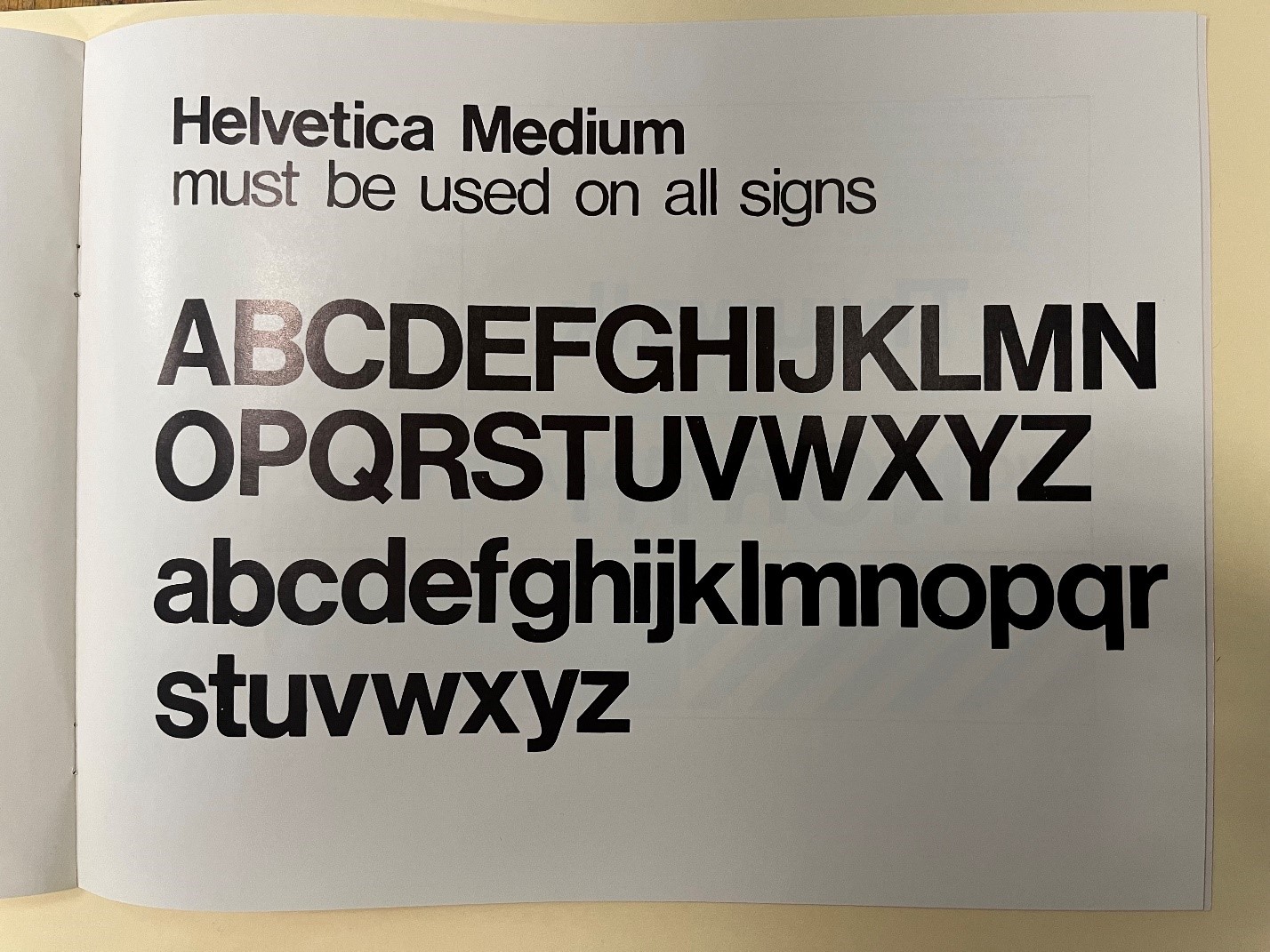

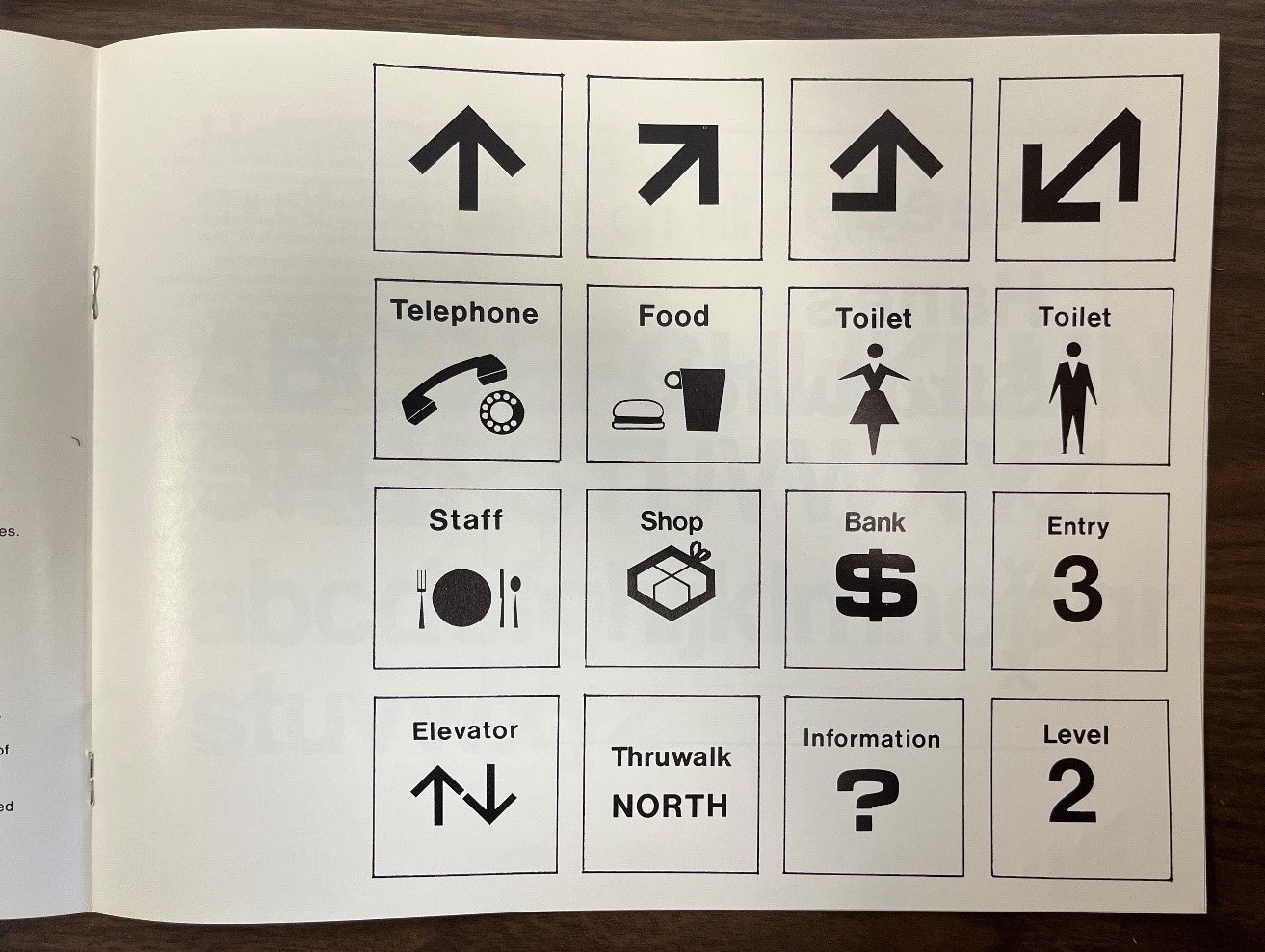

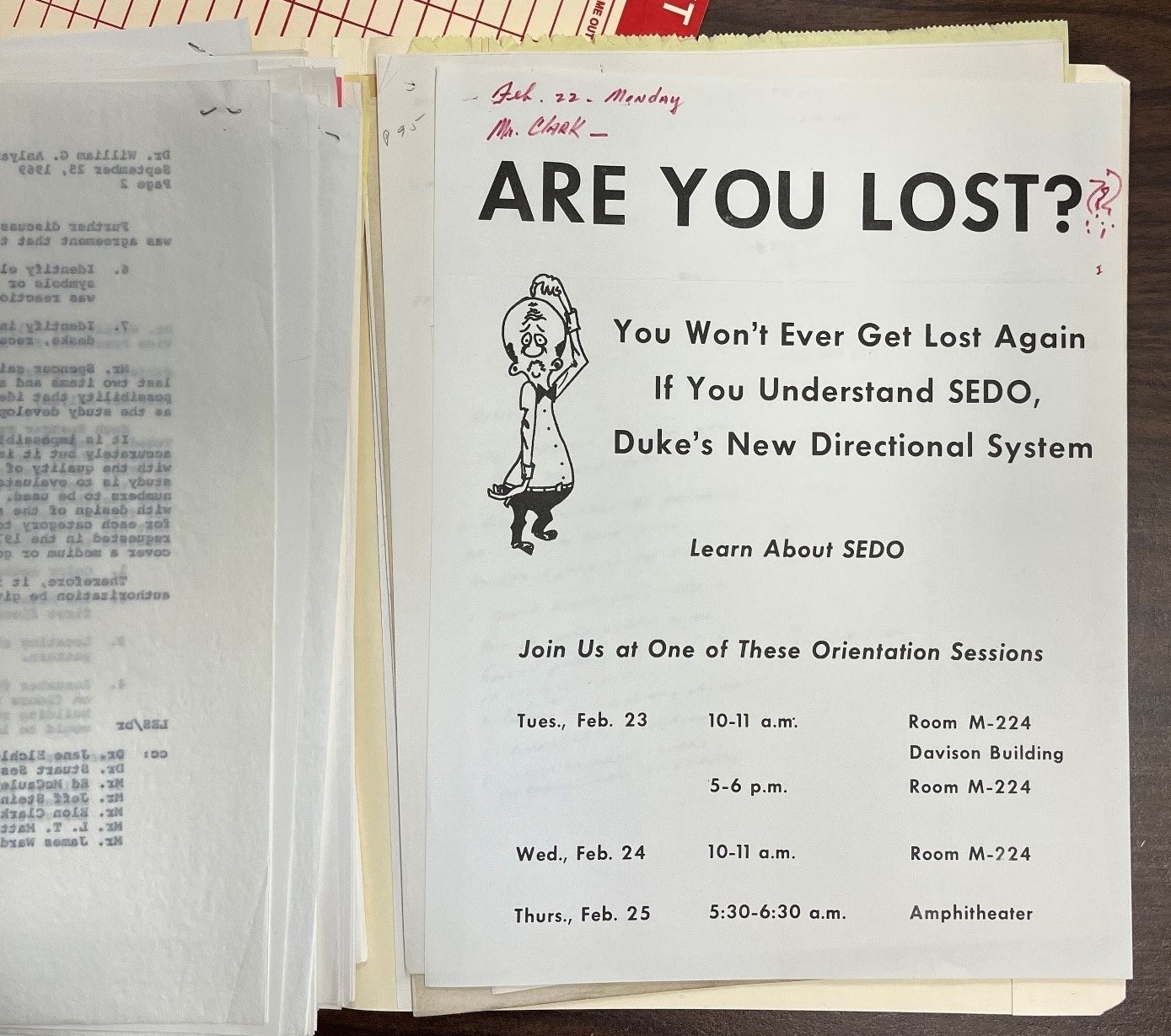

On March 5, 1971, a special issue of Intercom, the hospital’s weekly bulletin, devoted three of its four pages to the implementation of the new System of Environmental Direction and Orientation, or SEDO. SEDO was a mid-century modern wayfinding system based on eight color zones and hanging lighted signs, “similar to the idea behind routing systems at major airports,” designed to help visitors, patients, and employees better orient themselves through Duke University Medical Center (DUMC). The system was designed by industrial designer Hugh Spencer and the modular, triangular signs were manufactured and installed by Graphicon, Inc., of Greensboro, at a cost of roughly $60,000.

Throughout the 1960s, the hospital experienced rapid growth in both the services offered to its increasingly diverse patient population and its physical footprint. Prior to integration, wayfinding systems and signage posted throughout Duke Hospital, like other hospitals in the South, reflected the demarcation of spaces and services based on racial segregation. While the DUMC Archives holds a selection of photographs depicting segregated waiting areas for Black patients and families, finding clear visual evidence of Jim Crow-era wayfinding signage is challenging. As Elizabeth Guffey observes, “Despite their once pervasive presence in the American South, the little visual documentation left has led design historians to overlook this aspect of visual communications history” (42).

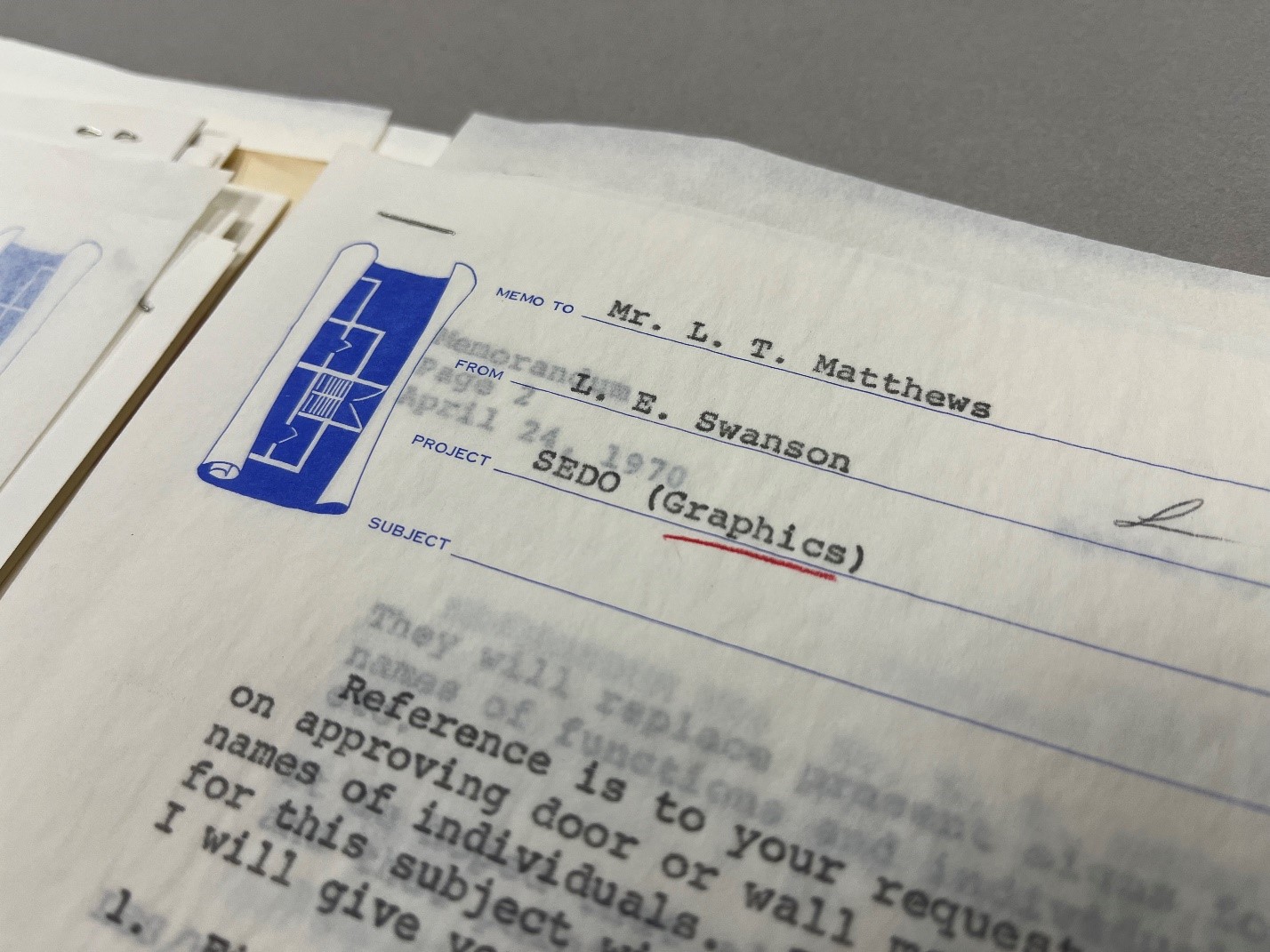

DUMC’s growth ultimately meant more buildings, more patients and visitors, and more confusion about how to navigate an increasingly complex medical center—or as Intercom puts it, “more people get lost in more places.” The papers of Elon Clark, coordinator and professor of the Department of Medical Illustration from 1934 to 1974, offer possible insight into wayfinding in the hospital immediately prior to SEDO: A map designed for the patients and families, dated March 1970, utilizes all 26 letters of the alphabet (and then starts over with AA through DD) to label the many sections of the hospital. The papers of Dr. Jane Elchlepp, who served as Vice President of Health Affairs, Planning, and Analysis, indicate the presence of idiosyncratically designed, hand painted signage posted throughout DUMC. Dr. Elchlepp was copied on one SEDO planning memo dated April 24, 1970, stating, “It is hoped that all [new] signs will conform to a standard and that painted signs and room numbers will be eliminated.”

The need for up-to-date, standardized, simplified signage was clear, and by early 1968, the medical center began to organize its resources for a new wayfinding system. Implementing such a system would require extensive planning and coordination from a variety of hospital administrators and stakeholders, including the Medical Center Planning Office, as well as employees with design and planning insight, such as Elon Clark, Robert Blake, and Dr. Jane Elchlepp. Going with an outside firm to design the signage, DUMC hired Hugh Spencer of Design Collective in 1969. A self-described “consulting ergonomist,” Spencer was an industrial designer active in Britain and Canada who employed mid-century modern design aesthetics in his work with electronics companies, car manufacturers, and the University of Toronto. Spencer also helped design the famed Project G Hi-Fi Stereo Cabinet for the Clairtone Sound Corporation in Toronto in 1963 (which, according to the Canadian Society of Decorative Arts, you just might recognize from the 1967 film, The Graduate).

In planning and implementing Spencer’s vision within a two-year time frame, tensions on the SEDO committee sometimes ran high. A copy of meeting minutes for a SEDO Evaluation Meeting held on July 19, 1971, reports that the rollout of SEDO “has been plagued with more than its fair share of problems. The nature of these problems varied from the conceptual to those related to implementation.” The “conceptual” problems likely allude to Hugh Spencer’s nebulous design ideas, which did not always align with the very practical needs of a hospital. The meeting minutes report then takes a lengthy left turn, pondering the philosophical distinctions between wayfinding and orientation (while also noting Spencer’s spelling and grammar idiosyncrasies):

According to Hugh Spencer’s CONSULTANT’S REPORT, the following are the Basic Principles of SEDO: ‘You are counselled to view this project as creating human orientation rather than the giving of directions for movement. To this purpose the establishment of an area identification by color will be effective while giving a number of extra benefits to a community with pschyosocial subdivisions.’ (Spencer’s spelling and grammar.)

Cutting through the philosophy, “a serious question arises,” concludes the report. “What does Duke University Medical Center want: A system telling people where they are in relation to something, or a system telling people where they want to go?”

Further “implementation” problems included difficulties in translating Spencer’s design ideas to local sign vendors and manufacturers, as well as strong feelings from staff and employees. The July 2, 1971, issue of Intercom included an insert: a questionnaire to evaluate “the new COLOR ZONE DIRECTIONAL SYSTEM.” Results of the questionnaire can be found in Elon Clark’s papers. Comments ran the gamut:

Drop it.

Tacky.

What about blind, color blind, and illiterates.

It's the best directional system we’ve used.

Probably a good system if one takes the time to learn it.

Adds charisma to Duke.

Older employees must use it for it to succeed.

I like the cubes on the ceiling at Memorial Hospital better.

Many do not understand that URO is urology; for someone not familiar with medical terminology, the signs do more harm than good.

In a memo dated March 18, 1970, Louis E. Swanson, Director of the Medical Center Planning Office, wrote to Dr. Jane Elchlepp that SEDO would be a “major innovation in the Medical Center and will get alot [sic] of attention and we can expect a variety of comments.” Swanson ends his memo with a careful musing about how SEDO might be communicated to and received by the wider hospital, perhaps articulating the hope and uncertainty that many people on the SEDO planning committee surely felt in planning a project of such magnitude: “Frankly, I think that most of the people that should know about the program are quite well informed, but equally frankly, I am never quite certain. This is my way of testing.”

References

Elizabeth Guffey. “Knowing Their Space: Signs of Jim Crow in the Segregated South.” Design Issues 28, no. 2 (Spring 2012): 41-60. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41427825.

Elon H. Clark Papers, Duke University Medical Center Archives.

Jane Elchlepp Papers, Duke University Medical Center Archives.

This blog post was contributed by Medical Center Archives Intern Kayla Cavenaugh.